My summer holiday this year was a road trip around Ireland with my sister. Our first stop was Belfast, which was I very excited about. I love street art, and I love the history of rebellion and resistance, so it felt like the perfect city for me. Although Irish history is not really taught in English schools, I was aware of the euphemistically named ‘Troubles’ in a vague sense that was heavily influenced by my parents’ perceptions of it; Mum in particular was a little bit nervous about us going to Northern Ireland, even 25 years after the Good Friday Agreement. We both made an effort to get to know the history a little bit better before going (I highly recommend the BBC documentary series Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland for a clear and concise account of the Troubles from start to ‘finish’). This is definitely one of those situations, however, where visiting a place gives you an insight that it is impossible to get from a book or a documentary.

I took my car over to Belfast from Scotland on the ferry, so we used a website to rent someone’s driveway whilst we were in the city (it’s a bit like AirBnB but for cars). When we arrived in the neighbourhood, we were taken aback by the loyalist flags and murals that adorned walls and lampposts. It is one thing to expect to find a lot of political murals in a city, it is quite another to turn a corner into a street an immediately be able to tell the political allegiances of it’s residents. Politics in Belfast is highly visible in public spaces of residential areas.

If I am asked about my national identity, I will say that I am British. But I wear my nationality loosely; I think nationalism causes a lot more problems than it solves, and it just isn’t that important to me. Walking around the loyalist areas of Belfast, I was confronted with an expression of British nationalism that felt quite alien to me, mainly in terms of how fierce it was. There were Union flags EVERYWHERE, alongside flags of Northern Ireland. There were murals dedication to Queen Elizabeth and King Charles, and other commemorated the losses of various parts of the British Army. I understand it; when a group feels threatened it is not uncommon to cling to that shared identity more tightly, but it is a very different Britishness to the one I am used too.

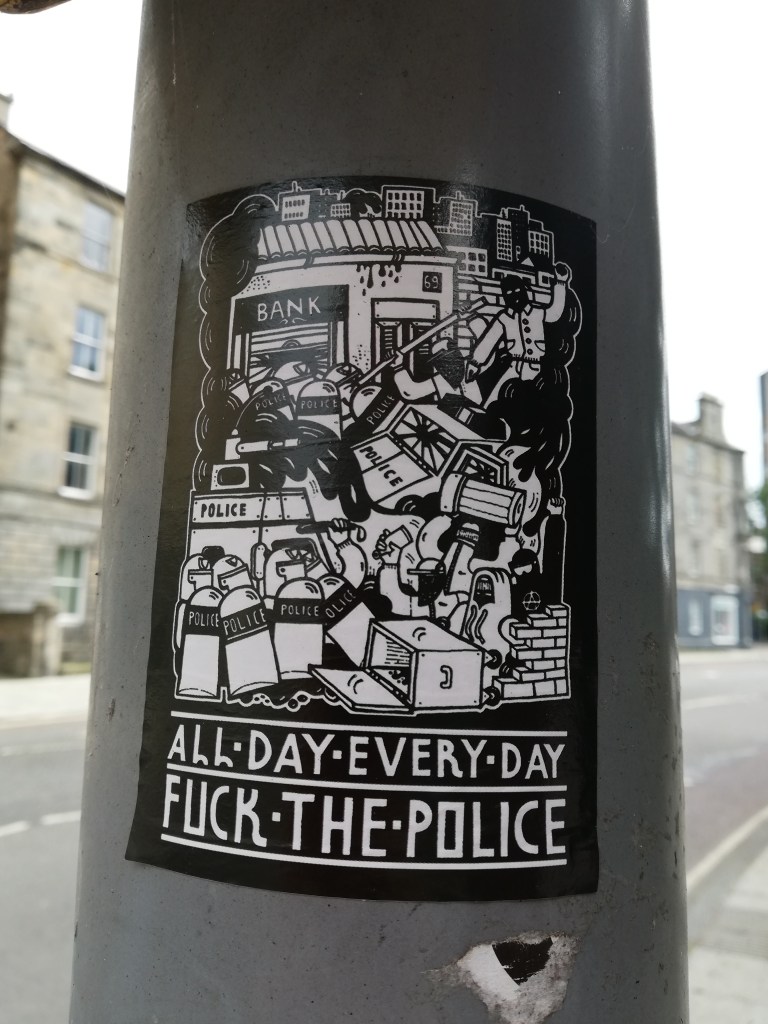

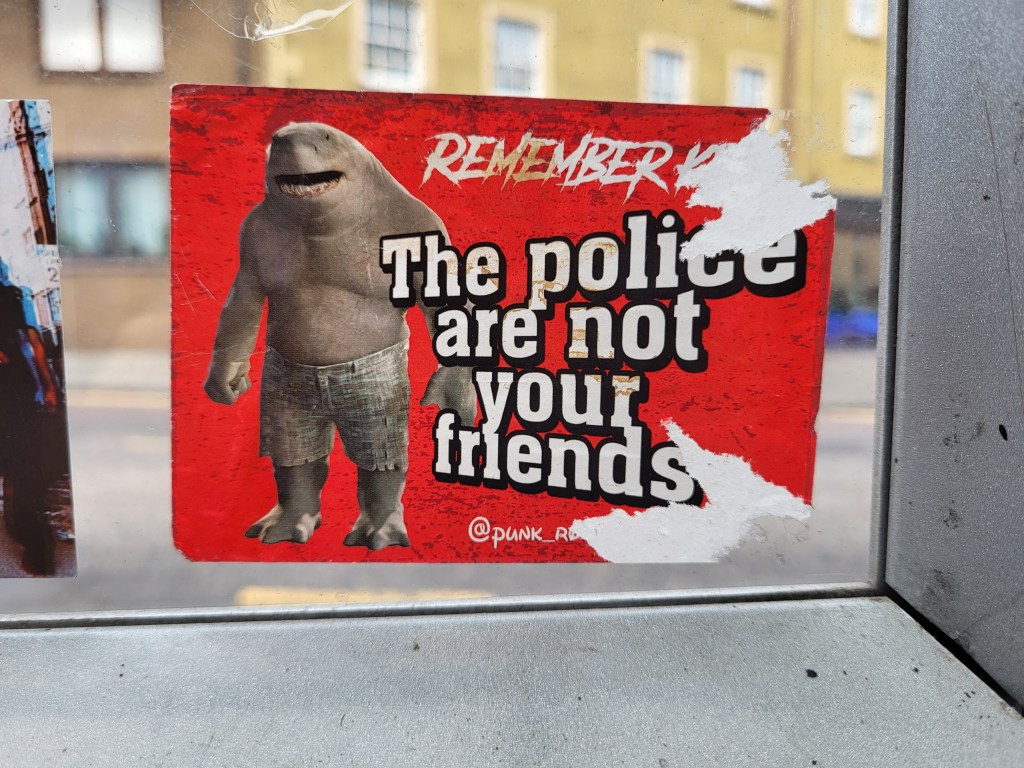

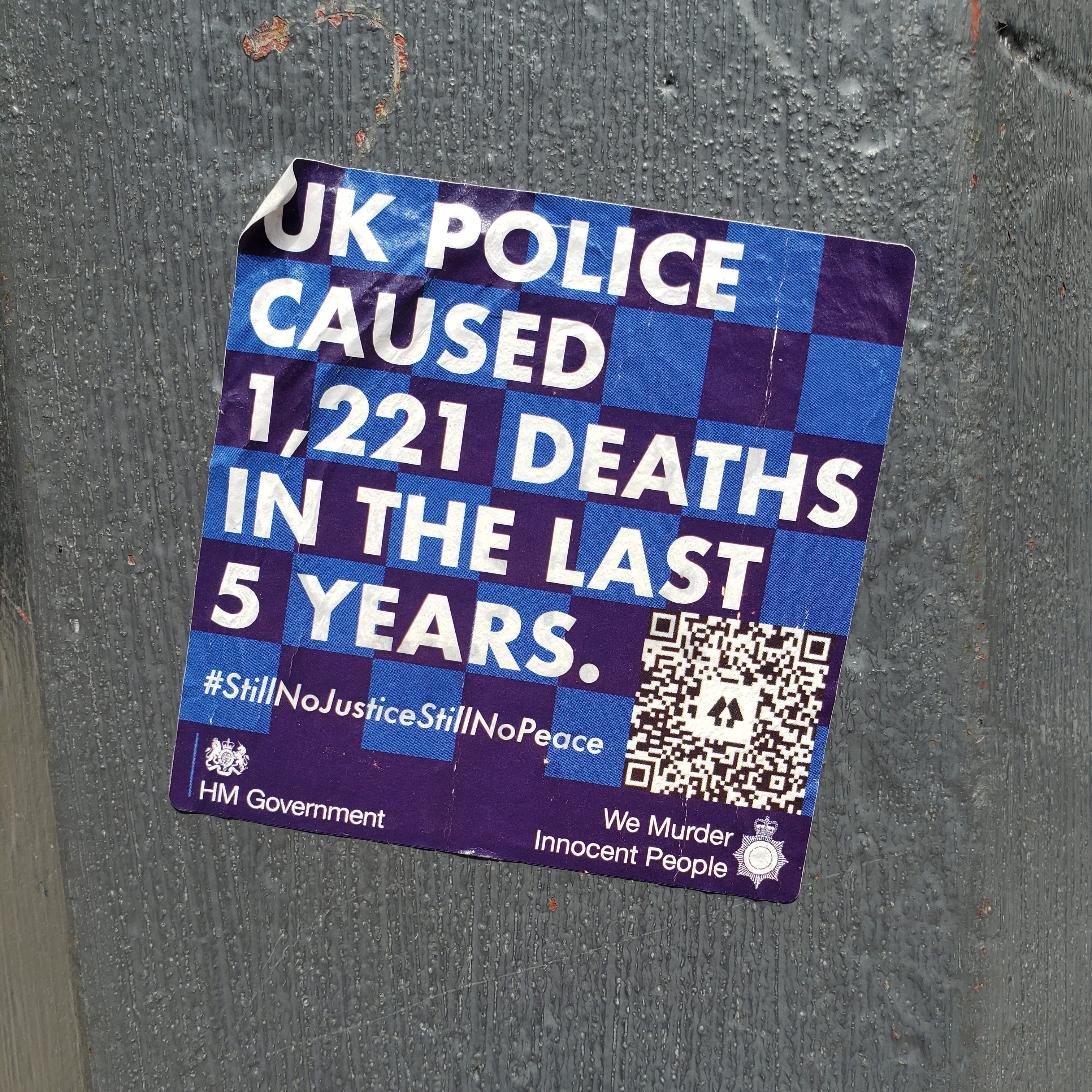

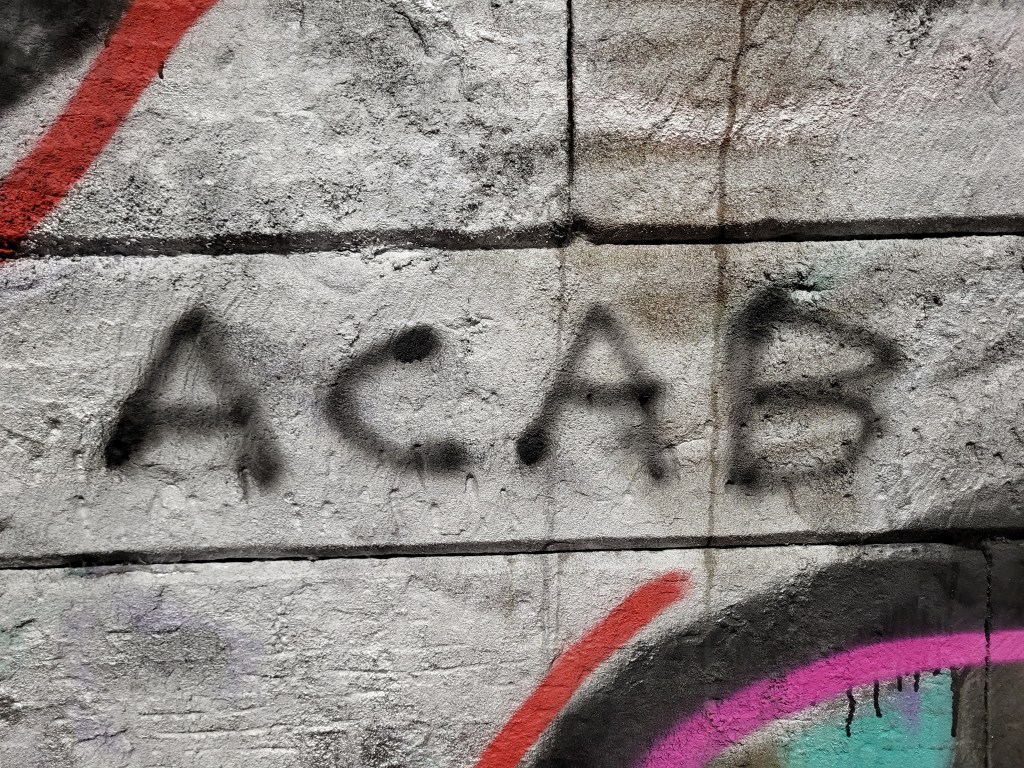

The Republican areas of Belfast express an Irish identity just as fiercely as the loyalist areas express a British identity. It is generally more outward-looking, expressing solidarity with international groups and campaigns such as Palestine and Black Lives Matter. There are not many things that Republicans and loyalists agree on (for example, loyalists tend to support Israel for a range of reasons, a significant one being that Republicans tend to support Palestine), so it is interesting that both groups are so prolific in their use of street art and murals. I would love to know more about the history of murals in Northern Ireland to gain a better understanding of how this situation developed (so if anyone knows of any good sources on this, please let me know!)

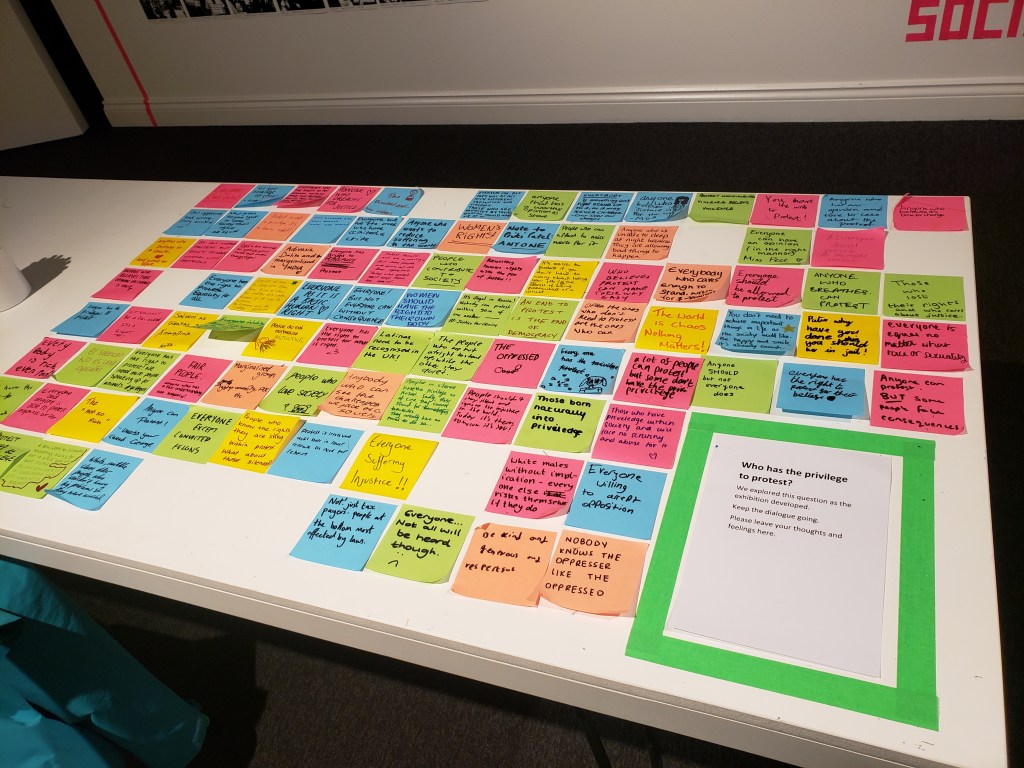

Separating many of the loyalist and Republican areas of Belfast are so-called Peace Walls. First built as temporary structures in 1969 at the beginning of the Troubles, many people in Northern Ireland still need them to feel safe in their neighbourhoods. I clearly remember the moment I first found out about them, at a conference during my PhD. I was shocked both that such structures exist in modern Britain, and that I didn’t know about them before; it is striking that they are not more widely known in the UK. Despite a commitment by the Northern Ireland Executive in 2013 to remove all Peace Walls by 2023, there are more today than there where when the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998. Cynics suggest that they are still in place because they are a popular tourist attraction in their own right. I would guess that the tensions caused by Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol have also slowed down their removal.

Given my interest in street art and political history, there wasn’t really any doubt that I would find Belfast a fascinating place. The city’s recent history and politics is inscribed into the urban fabric in a way that I have never seen anywhere else. What I was less prepared for was how much it would make me reflect on my own identity, and the gaps in my knowledge of the history of my own country.