Last week, I detailed my clunky and ad-hoc method for collecting and analysing old tweets. I have now finished my data collection (I read almost 26,000 tweets in total), so it seemed like a good time to reflect a little more on the experience of the process and what I found, rather than just how I did it. The tweets I read were all written during 4 days in November and December 2010. During this period a nationwide campaign was trying to persuade the British government not to make dramatic changes to the way that higher education was funded, which included raising university tuition fees to up to £9000 a year.

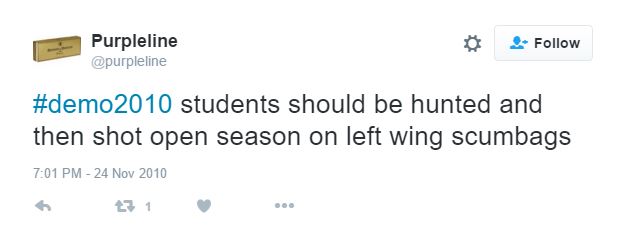

The Student Tuition Fee Protests in 2010 is the only one of my case studies (the others are the Gordon Riots (1780), the Hyde Park Railings Affair (1866), and the Battle of Cable Street (1936)) that I lived through and participated in. I have my opinions about the issues contested in each of the other case studies, but researching events that you yourself experienced is very different. I was a second year undergraduate in late 2010, my younger sister would be affected by the proposed increased fees, and I cared very much about what happened. Reading through tweets from the four days of protest in London brought back a lot of emotions; the desire to do something; hope that we could make a difference, disbelief that anyone thought the proposals were a good idea; betrayal at the Liberal Democrats’ U-turn; anger at those who dismissed students as ignorant, lazy and apathetic; all soured by the knowledge that we didn’t change anything. Compounding this is the tendency people have to be more arrogant and abrasive on the internet than they ever would be in person. Because of this some Tweets were quite offensive, and it was hard not to take it personally. I found myself fighting the urge to reply to some of the most irritating Tweets, repeatedly reminding myself how strange it would be to get a reply to something written 6 years ago. Reading the tweets caused me to re-live many of the feelings I experienced back in 2010, which meant that this research was often quite draining emotionally.

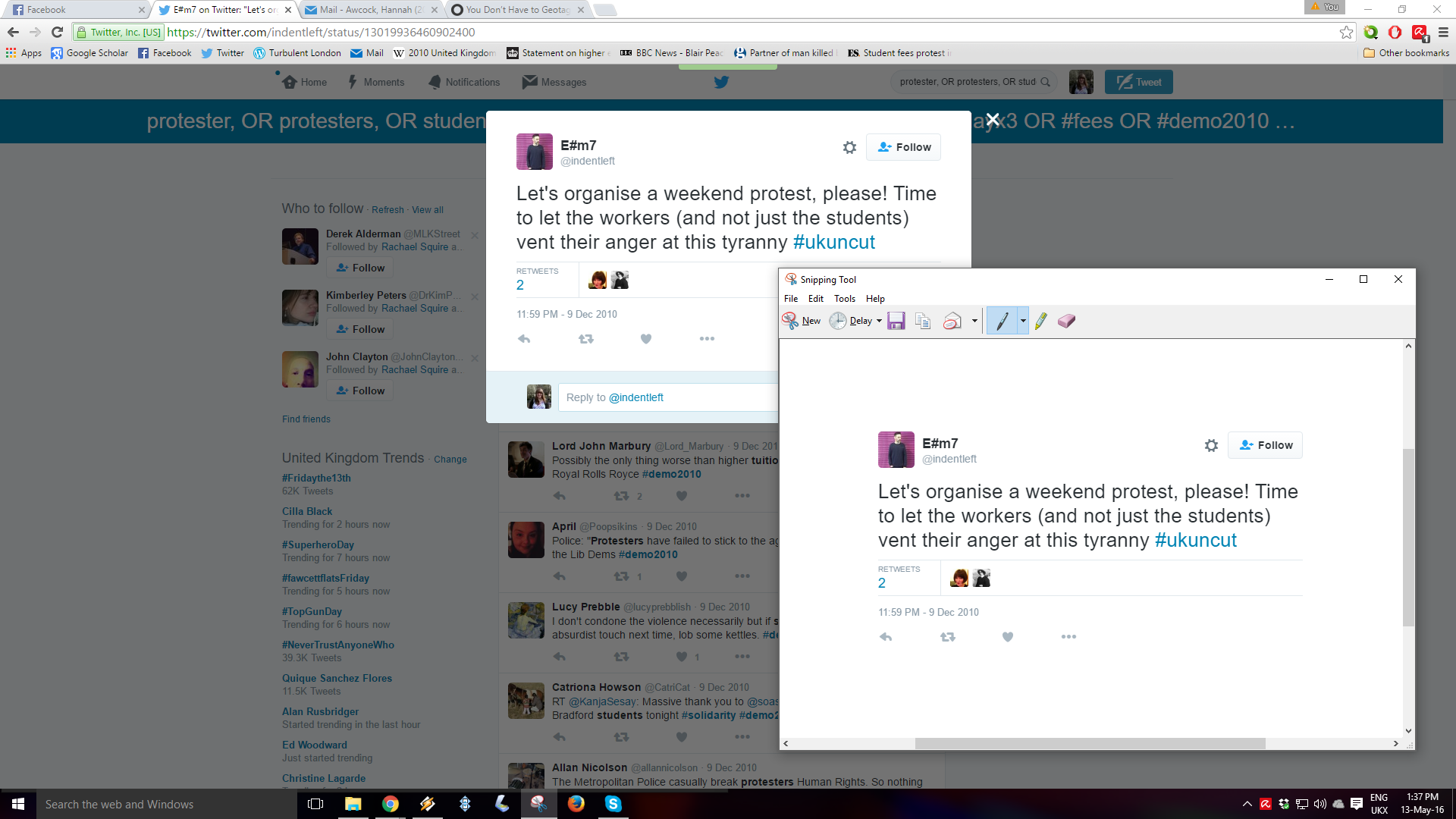

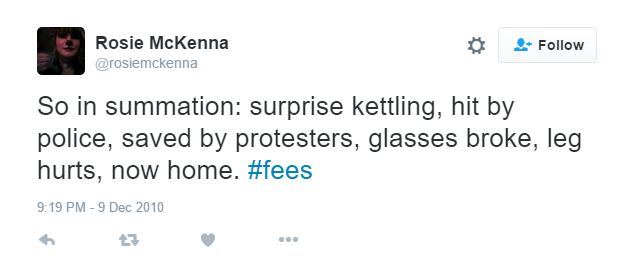

One of the biggest problems I have faced so far in my PhD research is that the further back in time you go, the less archival material there is which records the perspectives and experiences of ordinary people. This is a challenge for many historical researchers, but it has been particularly difficult for me because the wealthy elites don’t tend to be the people participating in protest and dissent. The internet is relatively accessible, with only 11% of British adults having never used the internet (Office of National Statistics, 2015). This does not mean that 89% of British people use Twitter, but it does give me the opportunity to see what ‘ordinary’ people were saying about the protests, which is a rare treat for me. Twitter revealed some wonderfully fine-grained details about the protests and what it was like to be there. For example, a woman called Rosie McKenna broke her glasses and hurt her leg whilst being kettled by police on the 9th of December. It was great to be able to develop such a clear picture of what it was like to be part of the protests, rather than having to rely heavily on imagination.

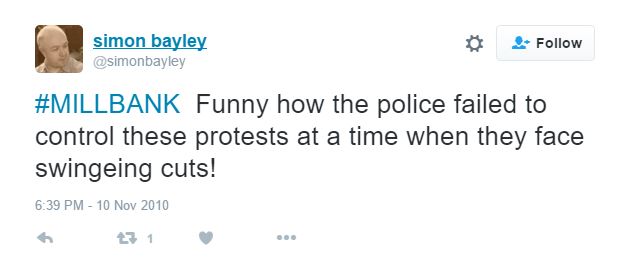

Another aspect of the research that I really enjoyed was seeing how various processes present in my other case studies played out through this modern technology. A common feature of protests and social movements is conspiracy theories; people speculate about who the ‘real’ organisers of a protest event are, or who might be manipulating the course of events to suit their own aims. The Gordon Riots, for example, were blamed on the American, Spanish or French governments. Scholars have argued that these theories developed because at that point it was not generally believed that the lower classes were capable of organising themselves in such a manner; they need someone to tell them what to do (Leon, 2011; Tackett; 2000). Conspiracy theories persist, however, despite modern society holding a less patronising view of the working and middle classes.One of the best known events of the 2010 Student Protests was the occupation of 30 Millbank, the building in which the Conservative Party campaign headquaters were housed. The response of the Metropolitan Police on this occasion was rather slow and inadequate. The most likely explanation is that they were surprised by the strength of feeling amongst the protesters, and had not prepared for trouble on that scale. However, it was suggested by some Twitter users that the police had deliberately responded slowly, because policing was facing its own budget cuts under the austerity regime, and wanted to demonstrate their usefulness to the government. The saying ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’ springs to mind…

After a long period of writing, I really enjoyed getting to doing some research again, and exploring a new source of data. Working with Twitter was tiring, physically as well as emotionally (I had to take regular breaks because of the strain on my eyes), but also very rewarding. It has provided me with evidence to back up my arguments, as well as leading me to develop some new ones, and I feel like my PhD will be stronger because I tried this new (to me) research method.

Sources and Further Reading

León, Pablo Sánchez. “Conceiving the Multitude: Eighteenth-Century Popular Riots and the Modern Language of Social Disorder.’ International Review of Social History 56, no. 3 (2011): 511–533.

Tackett, Timothy. “Conspiracy Obsession in a Time of Revolution: French Elites and the Origins of the Terror 1789–1792.” The American Historical Review, 105, no. 3 (2000): 691–713.