Turbulent Londoners is a series of posts about radical individuals in London’s history who contributed to the city’s contentious past. My definition of ‘Londoner’ is quite loose, anyone who has played a role in protest in the city can be included. Any suggestions for future Turbulent Londoners posts are very welcome. Next up is Mary Astell, a philosopher and writer who is considered by many to be England’s first feminist.

Mary Astell was a philosopher and writer from Newcastle whose ability to reason and argue made her a formidable force in intellectual circles in London in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Her advocacy of women’s education and her opinions on marriage has led her to be seen by many as England’s first feminist.

Mary was born in Newcastle on the 12th of November 1666 to an upper middle class family; her father managed a local coal company. Mary’s father died when she was 12, leaving her family with very little income. She received some education from her uncle, who was affiliated with a group of radical philosophers in Cambridge, but she also taught herself by reading widely. After her mother died in 1684, Mary moved to Chelsea in London, where she became acquainted with an influential and wealthy circle of women who helped her to develop and publish her work.

Between 1694 and 1709, Mary published a number of texts on a range of subjects, but she is best known for her arguments relating to women. She used her extensive understanding of philosophical ideas to argue that women were just as rational as men, and therefore just as deserving of education. After withdrawing from public life in 1709, Mary set up a charity school for girls in Chelsea. She devised the curriculum, putting her ideas into practice. Mary Astell died of cancer on the 11th of May 1731, leaving behind a lasting legacy.

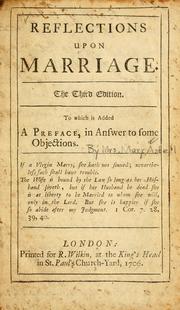

Mary’s first publication came out in 1694 and was entitled Serious Proposal to the Ladies for the Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest. In it, she proposes a female-only college, where women learn through reading and discussion, rather than a formal, hierarchical program of study. In Some Reflections Upon Marriage (1700), Mary continues advocating for women. She argues that an education would enable women to make better matrimonial choices, and be better prepared for married life. She warns women against making hasty choices when it came to marriage, and believed marriage should be based on friendship rather than necessity or fleeting attraction.

Mary’s ideas were groundbreaking for more than just their content. The way that she used philosophical ideas to support her arguments was unique, and she addressed women directly in her writing- talking to them, not about them. Her arguments disputed the Protestant belief, dominant at the time, that reason and emotion should be separate; for Mary, knowledge was intimately connected to happiness. Linked to this, one of the most frequent criticisms levelled against Mary’s ideas was that they were ‘too Catholic’; her plan for an all-female college sounded too much like a nunnery to be accepted by mainstream society. Mary’s ideas about women’s education caused substantial debate, and she was widely respected for her ability to debate freely and confidently with both men and women, but she did not receive widespread support.

“If all Men are born free, how is it that all Women are born slaves?”

Astell, Some Reflections Upon Marriage

The above quote is probably Mary Astell’s most famous, and it is easy to see why. This was a truly radical sentiment in the early eighteenth century. Not only did she express these radical ideas, Mary could support them with reasoned, rational, philosophical arguments. And she did all this at a time when there were few historical campaigners for women’s rights from which she could take inspiration and hope. As one of England’s first feminists she deserves to be remembered and celebrated, but she can also be for contemporary campaigners something she herself didn’t have- a role model.

Sources and Further Reading

Anon. ‘Astell, Mary.’ Encyclopaedia.com. Last modified 2005, accessed 28th July 2015. http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Mary_Astell.aspx

Anon. ‘Mary Astell.’ Wikipedia. Last modified 19th May 2015, accessed 28th July 2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Astell

Manzanedo, Julia Cabaleiro. ‘The Love of Knowledge: Mary Astell.’ Women’s Research Centre, University of Barcelona. Last modified 2004, accessed 28th July 2015. http://www.ub.edu/duoda/diferencia/html/en/secundario2.html

Sowaal, Alice. ‘Mary Astell.’ Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Last modified 12th August 2008, accessed 28th July 2015. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/astell/