On the 8th of November 2017, I gave the Postgraduate Voices talk at the Historical Geography Research Group’s (HGRG) annual postgraduate conference, Practising Historical Geography. I talked about my experience of academic communities, because of how important they have been to me during my PhD. I have decided to turn my talk into three blog posts, which I will publish here over the next few weeks. Part 1 was the about the various groups that make up my academic community. Part 2 is about the activities I have taken part in to build and maintain that community.

Seminars

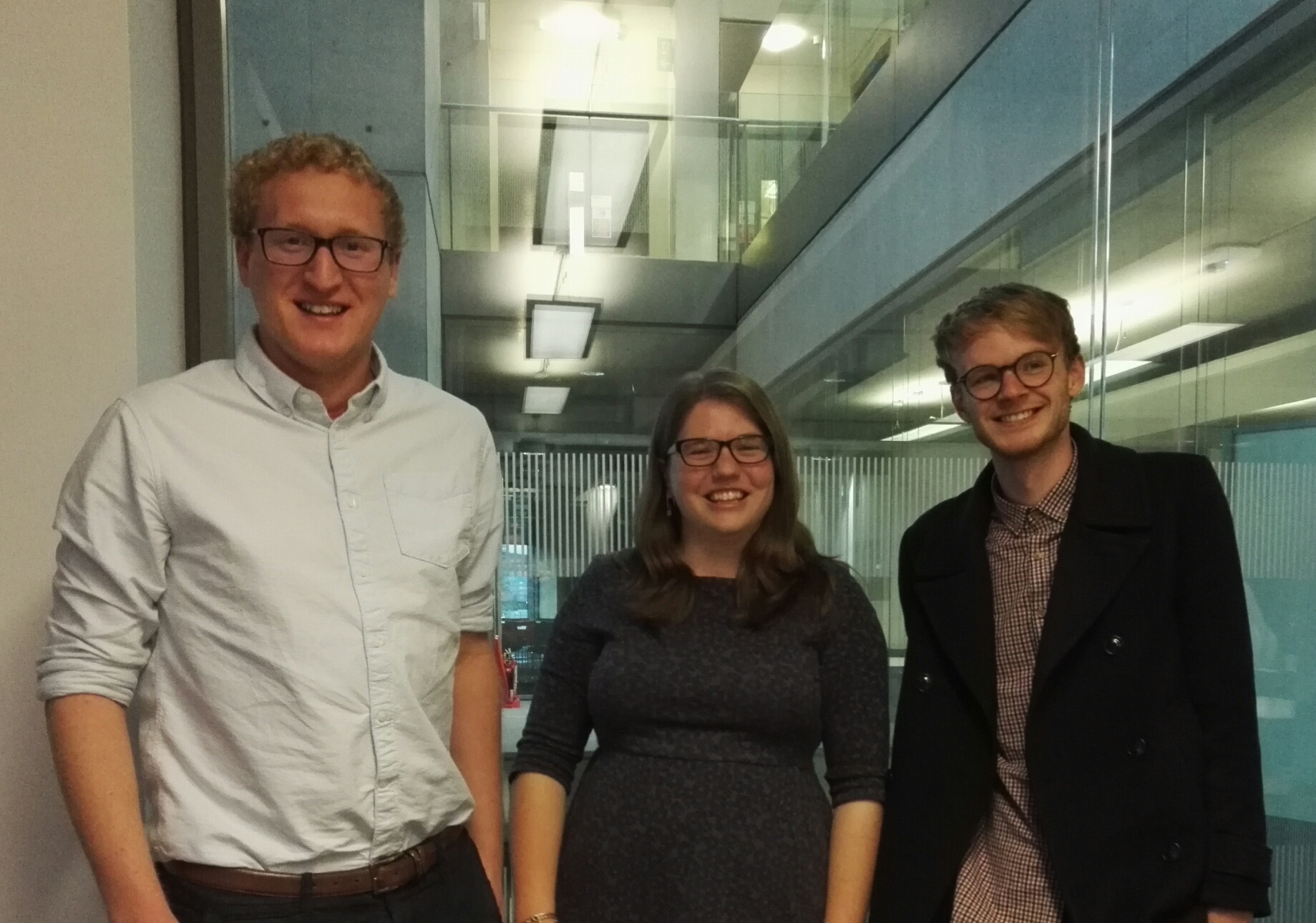

Just as there are probably different types of people in your academic community, there are different ways in which you can extend and strengthen it. Seminars are not just a way to hear about new research, they are also a way of participating in various communities. Attending departmental seminars are a good way for PhD students to be part of an academic department, particularly if you don’t have an office or desk in the university. The Social, Cultural and Historical Geography Research Group at Royal Holloway have a bi-weekly seminar series in central London called Landscape Surgery, for postgraduates and staff. It is a forum for Landscape Surgeons to share our work and ideas, and also sometimes features external speakers. Landscape Surgery has been a lifeline for me during my PhD. The Human Geography postgraduates at Royal Holloway are quite geographically dispersed—most of us don’t go into the department on a regular basis. So Landscape Surgery was frequently my only contact with an academic community. It helped me to maintain my connection to the staff and students of the Royal Holloway Geography Department.

However, seminars can also introduce you to communities that go beyond your department. Another important seminar series for me is the London Group of Historical Geographers, which also meets every other week in central London. The seminars, and the trip to Olivelli’s Italian restaurant for dinner afterwards, have really helped me to develop my academic social skills over the years. The dinners in particular have introduced me to a range of historians and historical geographers in a less formal setting, which made it easier for me to actually carry on a semi-intelligent conversation.

Conferences

I have been to quite a few conferences during my PhD, from small-ish ones like Practising Historical Geography to massive international conferences like the RGS Annual Conference and the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers. Like seminars, attending conferences is a brilliant way of meeting other academics. If you are presenting a paper, people will often come and introduce themselves to you, and it also serves as something to talk about, thus helping to avoid awkward silences or introductions. I have found organising conference sessions to be even more helpful. Putting out a Call for Papers connects you with people who have similar research interests. Or, you can invite people to take part in your session, providing you with a reason to get in touch with that Professor that you’ve always wanted to talk to. I’m convening a session at the International Conference of Historical Geographers in Warsaw next year. The prospect that I would get silence in response to my invitations and Call for Papers was a scary one, but I actually got a fantastic response. So I’m making new connections and extending my academic community, as well as building on my pre-existing connections with excellent academics and the conference is still months away.

The point that conferences help to maintain and develop pre-existing connections as well as making new ones is important. There are a number of my peers from all over the country that I only ever really see at conferences, so they represent a good chance to catch up. Being part of a community isn’t just about making new connections and meeting new people, it’s also about staying connected to people you’ve already met but don’t see very often.

Research Groups

Research Groups are open, welcoming, and often actively encourage the participation of postgraduates. They also organise events that give you the chance to participate in academic communities.

Research groups also give you the opportunity to give back to your academic community. For just over a year, I have been a member of the committee of the Digital Geographies Working Group. Serving on a Committee provides you with the opportunity to meet new people, and work with those you already know, but it also allows you to develop new skills, such as organising academic events, managing budgets and accounts, or running a website. I helped to organise the first annual Digital Geographies Symposium last year. It was a steep learning curve, but it was also great fun.

Social Media

Not every academic makes use of social media, but I have found it to be very beneficial. I am active on Twitter, and I also run this blog. Twitter has allowed me to make new connections, and stay in touch with people in between conferences. Twitter can also act as a sort of leveller, making it less intimidating to approach and start a discussion with a big name.

As well as being something that I really enjoy doing, and allowing me to toy with the concept of impact, my blog gives me a presence on the internet beyond your normal Twitter account or departmental webpage. If someone wanted to, they could get a good sense of who I am and what my research interests are from Turbulent London. I am also keen to publish contributions from guest authors, which is another reason to make connections with people that you perhaps otherwise wouldn’t. Although not universal, there is no doubt that social media has changed the way that academics interact. I personally think it is a great way to participate in the academic community.

Participating in academic networks can be time consuming, but it is incredibly worthwhile; you can learn new skills, cement your place in academic communities, and it is great fun. In is not all plain sailing however; in Part 3 of The Value of Academic Communities, I will talk about some of the challenges I have faced whilst building my academic communities.