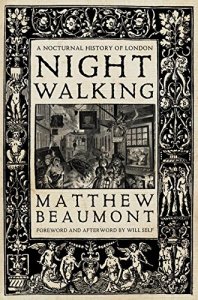

Matthew Beaumont. Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London. London: Verso, 2015. £9.99

Nightwalking by Matthew Beaumont is an exploration of London at night through the eyes of the men (and it is all men) who wrote about it. Starting with Chaucer, Beaumont traces evolving societal attitudes to night time and darkness in the city. He ends the book with Dickens (well, sort of- Edgar Allen Poe features heavily in the conclusion), “the great heroic and neurotic nightwalker of the nineteenth century” (Beaumont, 2015; p.6). The writers Beaumont studies walked the line between polite society and the world of the social outcasts; the prostitutes, criminals, orphans, and homeless who inhabited London’s streets after dark. Some writers managed the balance better than others.

Who walks the streets alone at night? The sad, the mad, the bad. The lost, the lonely. The hypomanic, the catatonic. The sleepless, the homeless. All the city’s internal exiles.

Beaumont, 2015; p.3

When I first got Nightwalking, I was a little disappointed to realise that it had a literary focus. I like to read, but I’m not a fan of literary analysis; perhaps there are too many bad memories from GCSE and A-Level English Literature. I thought Nightwalking was a straight social history, and I wasn’t sure I would enjoy the literary angle.

I needn’t have worried. Beaumont uses the cultural history of the London night to explore its social, political and economic history. He strikes a nice balance between detailed textual analysis and wider contextual discussion. The social and legal discourses surrounding those who wander the streets of the city at night have developed over time, but in an uneven manner. For hundreds of years, being caught outside after dark was a criminal offence. As society and technology developed, the night became a space of recreation, initially just for the wealthy; the evolution of cheap and effective street lighting is one factor that contributed to this process. Although the legal restrictions faded, moral restrictions remained, dictating which kinds of activity, and which kinds of people, were acceptable on London’s streets after dark.

London’s writers were drawn to this moral ambiguity, taking to the streets at night in order to better understand the city or themselves, to have a good time, and sometimes because they had no choice. Men such as Chaucer, Shakespeare, Johnson, Blake, and Dickens “used the night as a means of creatively thinking the limits of an increasingly enlightened, rationalist culture” (Beaumont, 2015; p.10). Beaumont balances all the contradictory and sometimes vague associations and motivations for nightwalking well, explaining his arguments in a clear and concise manner. It is obvious to me that Beaumont is an academic, and that the book is based on extensive scholarly research, but I don’t think that the book would be unapproachable to non-academics, although another reviewer has said his style can be “cloudily academic.”

Nightwalking is a well-researched, well-reasoned book that manages to tell a complicated story in a way that is easy to follow. I can see this book being useful to students of English Literature and History alike, but I would also recommend it to those who just enjoy reading a good book.