Turbulent Londoners is a series of posts about radical individuals in London’s history who contributed to the city’s contentious past, with a particular focus of women, whose contribution to history is often overlooked. My definition of ‘Londoner’ is quite loose, anyone who has played a role in protest in the city can be included. Any suggestions for future Turbulent Londoners posts are very welcome. The next Turbulent Londoner is Katherine Chidley, an activist for religious toleration and a leader of Leveller women.

The further back in time you go, the harder it is to find out about individuals who weren’t members of the aristocracy, especially if they were women. There are some women who managed to leave a trace in the archives, often thanks to their radicalism, such as Mary Astell (1666-1731) and Elizabeth Elstob (1683-1756). Katherine Chidley lived even earlier, between the 1590s and about 1653. She was a religious dissenter and a key member of the radical networks that preceded the Levellers, as well as the Levellers themselves.

The first time Katherine Chidley appears in the historical record she is already married with seven children. Along with her husband Daniel, she set up an independent church in Shrewsbury in the 1620s which clashed with the local established church. At this point everyone was required by law to be a member of the Church of England, and there was no toleration for anyone who wanted to worship differently. Radical religious sects had an emphasis on church democracy, which meant that women played more of a role than in other sectors of society, as preachers, prophetesses and petitioners. In 1626 Katherine was charged with refusing to attend church, along with 18 others. She also got in trouble for refusing to attend church for an obligatory cleansing after childbirth.

The Chidley family moved to London in 1629. Katherine’s husband became a member of Haberdashers Company, and their oldest son Samuel started an apprenticeship in 1634 . The family’s views became more radical and separatist after they moved to London. Daniel and Samuel helped to establish a dissenting congregation headed by John Duppa. The congregation claimed the right to choose their own pastor not paid for by Church funds. The congregation itself was illegal, and its members faced harassment, arrest, and imprisonment.

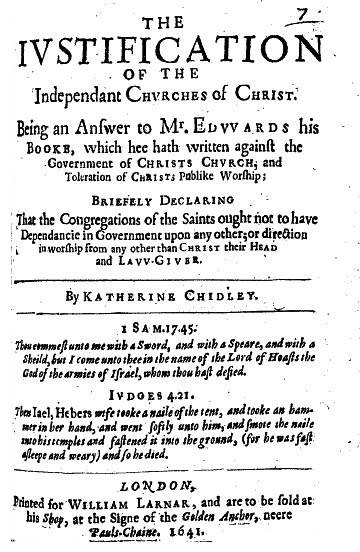

Katherine authored several pamphlets in defence of religious radicalism. Thomas Edwards was a popular puritan preacher at the time, who argued against religious Independents from a conservative Presbyterian perspective. In 1641 he published a pamphlet, addressed to Parliament, arguing against religious tolerance. Katherine was the first to attack Edwards’ arguments in print, in her first pamphlet. It was called The Justification of the Independent Churches of Christ, and it was very unusual for a woman to take such a step. Edwards ignored her response, embarrassed to have been so publicly confronted by a woman.

Katherine’s concept of toleration was broad, even extending to Jews and Anabaptists, groups that faced extreme discrimination at the time. She believed that everyone should be able to organise their own churches if they so desired. Katherine did view women as weak and inferior to men, but she defended a wife’s right to make her own decisions about religion. She also frequently discussed examples of God using the weak or socially inferior to defeat the powerful and ungodly. Katherine may not have been a feminist by modern standards, but her views were radical for the time. She published 2 more pamphlets in 1645. The first was another attack on Thomas Edwards, called A New-Yeares-Gift, or a Brief Exhortation to Mr. Thomas Edwards; that he may breake off his old sins, in the old yeare, and begin the New yeare, with new fruits of Love, first to God, and then to his Brethren. They didn’t really go for snappy titles in the seventeenth century.

When the Leveller network emerged, Katherine became a leader of Leveller women. The Levellers were a radical movement that argued for popular sovereignty, equality before the law, and religious toleration. They gained significant popular support between the First and Second English Civil Wars, but were considered too radical even for Oliver Cromwell and the Protectorate. Daniel died in 1649, and it seems as though Katherine took over his business with the help of Samuel. As well as being a religious radical, she was also a successful businesswoman, handling government contracts worth significant amounts. In 1649 Katherine was one of the organisers, and probably the author, of a women’s petition to free four Leveller leaders from the Tower of London. In 1653, when Leveller leader John Lilburne was again imprisoned and charged with treason, Katherine led a group of 12 women to Parliament to present a petition demanding his release signed by 6000 women.

Although much of her activism involved male family members, and she believed that women were inferior to men, Katherine Chidley was a fierce woman who fought for the right to make her own decisions about how she worshipped. There is no trace of her in the historical record after 1653, so the rest of her life is a mystery.

Sources and Further Reading

Rees, John. The Leveller Revolution: Radical Political Organisation in England, 1640-1650. London: Verso, 2016.

Wikipedia, “Katherine Chidley.” Last modified 28 May 2017, accessed 15 August 2017. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katherine_Chidley