Turbulent Londoners is a series of posts about radical individuals in London’s history who contributed to the city’s contentious past, with a particular focus of women, whose contribution to history is often overlooked. My definition of ‘Londoner’ is quite loose, anyone who has played a role in protest in the city can be included. Any suggestions for future Turbulent Londoners posts are very welcome. To celebrate the centenary of the Representation of the People Act, all of the Turbulent Londoners featured in 2018 will have been involved in the campaign for women’s suffrage. Next up is Dora Montefiore, a journalist, pamphleteer and socialist.

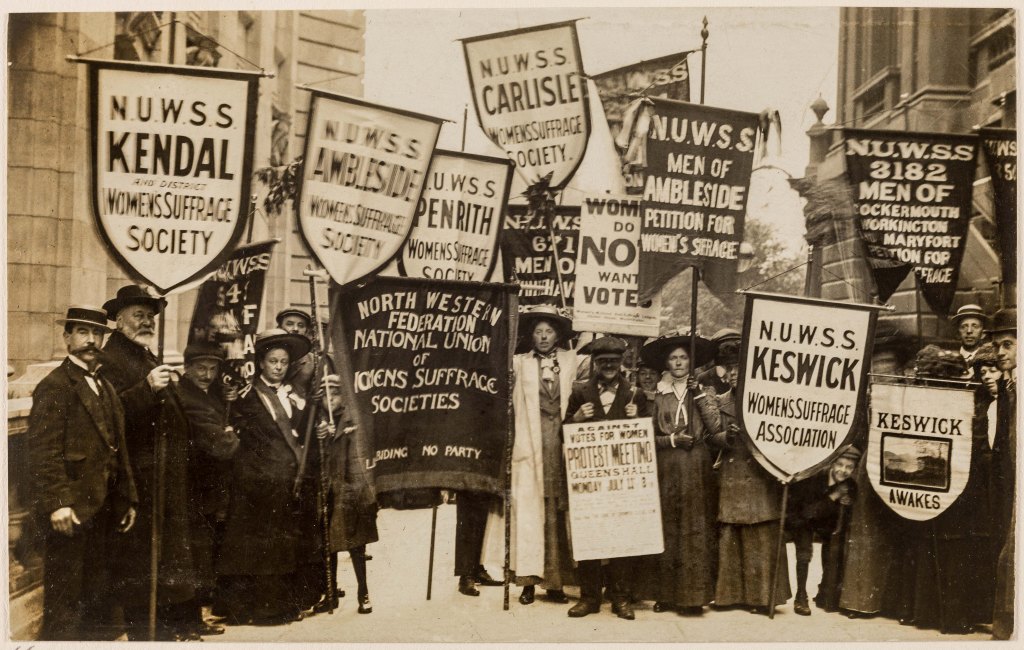

The women who campaigned for the right to vote are usually divided into two camps: suffragettes and suffragists. Some women, however, blurred the lines. Dora Montefiore was one such woman, who was a member of a dizzying number of groups, including the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the Women’s Tax Resistance League, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the Adult Suffrage Society, the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), the Social Democratic Federation/British Socialist Party, and the Communist Party of Great Britain. She held prominent positions in some of these groups, and also contributed her skills as a writer to the women’s movement and socialism.

Born Dora Fuller in Surrey on the 20th December 1851 into a wealthy family, Dora had a privileged childhood, with a good education from governesses and a private school in Brighton. In 1874, she moved to Sydney to help her brother’s wife. She met wealthy merchant George Barrow Montefiore, and they were married in February 1881. They had two children in 1883 and 1887. George died in 1889, and Dora discovered that she didn’t have the automatic right to become guardian of her own children, it had to be specified in her husband’s will. It was this stark inequality that converted Dora into a women’s rights campaigner. In March 1891, she held the first meeting of the Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales at her house.

In 1892 Dora left Australia, spending a few years in Paris before settling in England. She threw herself into the women’s movement here, serving on the executive of the NUWSS under Millicent Garrett Fawcett and founding the Women’s Tax Resistance League in 1897. She refused to pay taxes during the Boer War (1899-1902) on the grounds that the money would be used to fund a war that she had no say in. Bailiffs seized and auctioned her goods to cover the tax bill.

When the WSPU was formed Dora also became an enthusiastic member. She was good friends with Minnie Baldock, and was a regular speaker at the Canning Town branch of the WSPU, which was the first branch in East London, founded by Minnie. In 1906, Dora refused to pay her taxes again, this time until women were given the right to vote. In May and June, she barricaded herself into her house in Hammersmith for 6 weeks to prevent bailiffs seizing her goods. She hung a banner on the wall that read: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” In October, she was arrested and imprisoned, along with several others, for demanding the right to vote in the lobby of the House of Commons.

Dora was nothing if not principled, however, and by the end of 1906 she had left the WSPU because she disagreed with it’s autocratic structure that gave significant power to a small group of wealthy women. The following year, she joined the Adult Suffrage Society, and was elected honorary secretary in 1909. The Adult Suffrage Society believed that a limited franchise would disadvantage the working classes and might delay universal adult suffrage, rejecting the idea that is was an important stepping stone.

After leaving the WSPU, Dora remained close to Sylvia Pankhurst, who shared her belief in socialism. Dora was a longstanding member of the Social Democratic Federation, later the British Socialist Party. She advocated a socialism that was also concerned with women’s issues and in 1904, she helped establish the party’s women’s organisation. She left the group in 1912 because of her opposition to militarism. When the Communist Party of Great Britain was formed in 1920, Dora, aged 69, was elected to the provisional council.

Dora was a journalist, writer, and pamphleteer. In 1898, she published a book of poetry called Singings through the Dark. From 1902 to 1906 she wrote a women’s column in The New Age, and she contributed to the Social Democratic Foundation’s journal, Justice. She would later write for the Daily Herald and New York Call. In 1911, whilst in Australia visiting her son, she edited the International Socialist Review of Australasia when its owner fell ill. Most of the pamphlets she wrote were about women and socialism. For example, in 1907 she wrote Some Words to Socialist Women.

In 1921, Dora’s son died from the effects of mustard gas poisoning he had received fighting on the Western Front during the war. She had to promise not to engage in Communist campaigning in order to be allowed to visit her daughter-in-law and grandchildren in Australia. Despite this promise, Dora used the time to make connections with the Australian communist movement; in 1924, she represented the Communist Party of Australia in Moscow at the fifth World Congress of the Communist International. She had long taken an international approach to her campaigning, attending conferences in Europe, the United States, Australia, and South Africa.

Dora Montefiore died at her home in Hastings, Sussex, on the 21st of December 1933. She is commemorated on the plinth of Millicent Garrett Fawcett’s statue in Parliament Square. She was a committed socialist and suffrage campaigner, and did what she thought was right, even when that meant leaving groups that she had previously devoted herself to. She also pioneered one of the lesser-known tactics of the women’s suffrage movement, tax resistance. It was a strategy that combined civil disobedience with non-violence, and became an important tool in the suffrage arsenal. She is not well-known today, that does not make her contribution any less significant.

Sources and Further Reading

LBHF Libraries. “Local Suffragettes.” LBHF Libraries and Archives. Last modified March 23 2018, accessed September 27 2022. Available at: https://lbhflibraries.wordpress.com/2018/03/23/local-suffragettes/

Matgamna, Sean. “Dora Montefiore: A Half-forgotten Socialist Feminist.” Marxists.org. No date, accessed June 15, 2018. Available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/montefiore/biography.htm

Simkin, John. “Adult Suffrage Society.” Spartacus Educational. Last modified August 2014, accessed June 15, 2018. Available at http://spartacus-educational.com/Wadult.htm

Simkin, Jon. “Dora Montefiore.” Spartacus Educational. Last modified February 2015, accessed June 15, 2018. Available at http://spartacus-educational.com/Wmontefefiore.htm

Wikipedia. “Dora Montefiore. Last modified April 26, 2018, accessed June 15, 2018. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Montefiore

Working Class Movement Library. “Dora Montefiore.” No date, accessed June 15, 2018. Available at https://www.wcml.org.uk/our-collections/activists/dora-montefiore/