Turbulent Londoners is a series of posts about radical individuals in London’s history who contributed to the city’s contentious past, with a particular focus on women, whose contribution to history is often overlooked. My definition of ‘Londoner’ is quite loose, anyone who has played a role in protest in the city can be included. Any suggestions for future Turbulent Londoners posts are very welcome. To celebrate the centenary of the Representation of the People Act, all of the Turbulent Londoners featured in 2018 will have been involved in the campaign for women’s suffrage. This post is about Flora Drummond, a WSPU organiser who was nicknamed ‘The General.’

Flora Drummond (nee. Gibson, later Simpson) was a talented organiser and public speaker. She became involved in the suffrage movement after a personal experience of injustice, and went on to become one of the most well-known organisers in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Thanks to her effective organisation skills she became known as ‘the General’ and embraced this nickname, leading suffragette marches dressed in military style uniform and riding a horse.

Flora Gibson was born on 4th August 1878, the daughter of a tailor. Although she was born in Manchester, she grew up on the Isle of Arran in Scotland. When she was 14 she left school and moved to Glasgow to continue her education. She completed the qualification to be a postmistress, but was denied a job because of new regulations that required workers to be at least 5 foot 2 inches tall. Flora was 5 foot 1 inch. She felt this injustice very deeply, believing that the rule discriminated against women because they were shorter on average. Despite this setback, she went on to get further qualifications in short hand and typing.

In 1898, Flora married Joseph Drummond, and the couple moved to Manchester. Both were active in the Fabian Society and International Labour Party. Flora worked in various factories, so she could better understand what life was like for the women who had no choice but to work there. When her husband became unemployed, however, Flora became the sole breadwinner and worked as manager at the Oliver Typewriter Company.

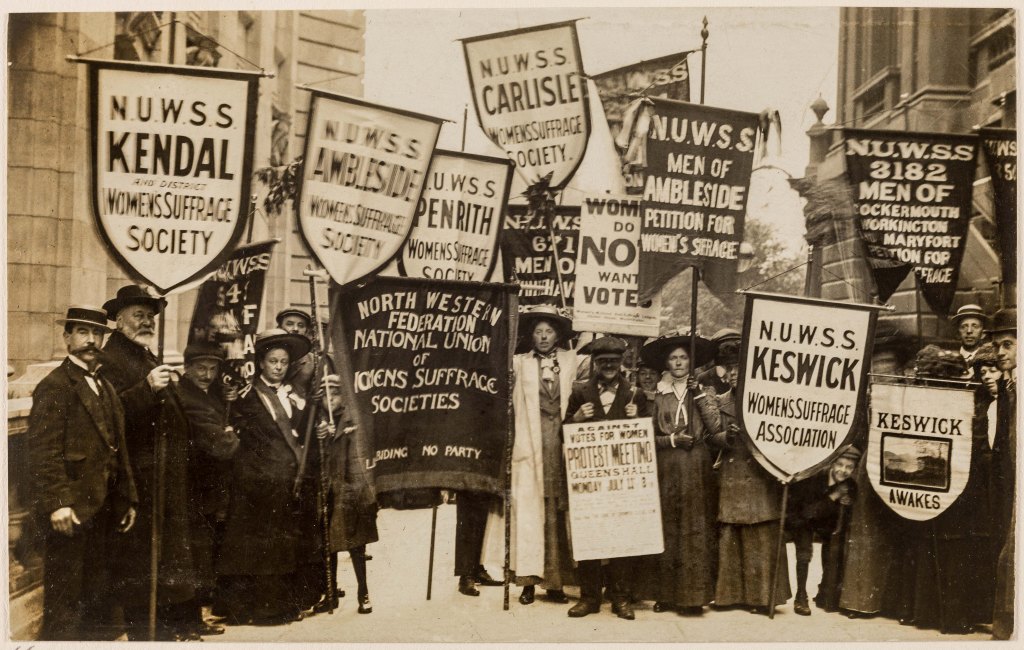

Flora joined the WSPU in Manchester, and moved with it down to London in 1906, when she became a paid full-time organiser, along with Annie Kenney and Minnie Baldock. Her extensive organisational skills were quickly recognised by the WSPU; in 1908 she was put in charge of the group’s headquarters in Clement’s Inn. She was popular and innovative in this role. Flora also had a flair for dramatic protests. That same year, she hired a boat and floated on the Thames outside the Houses of Parliament, addressing the MPs that were sat on the riverside terrace. In October, Flora was a key organiser of a rally in Trafalgar Square. Because of her role, she was arrested for inciting suffragettes to rush the House of Commons, and was sentenced to 3 months in prison, alongside Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. She was released early when it was discovered she was pregnant. Flora would be imprisoned a total of 9 times for the suffrage cause, and went on hunger strike on several of those occasions. It was around this time that Flora acquired the nickname ‘the General,’ for her enthusiastic and effective organisation skills. She embraced the nickname, and began wearing a military style uniform on demonstrations.

In October 1909, Flora moved to Glasgow and organised the first militant pro-suffrage march in Edinburgh. She also ran the WSPU’s general election campaign in 1910, before returning to London in 1911. Flora was captain of the WSPU’s Cycling Scouts. Based in London, this group of women would cycle out to the surrounding countryside to give pro-suffrage speeches. By 1914, Flora’s health was suffering from repeated imprisonments and hunger strikes. She returned to the Isle of Arran to recuperate, but came back to London when war broke out. From this point onward, however, she focused on public speaking and administration, avoiding direct action in order to minimise her chances of arrest; her organisational skills meant she was more useful to the cause outside of prison anyway. During the First World War, Flora stayed loyal to Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and threw herself behind the war effort. Proving she had abandoned the left-wing politics of her youth, Flora toured the country trying to persuade trade unionists not to strike.

In 1918, Flora helped Christabel in her unsuccessful election campaign standing for the Women’s Party in Smethick. In 1922, she divorced Joseph and later married Alan Simpson. Flora co-founded the Women’s Guild of Empire, a right-wing campaign group opposed to both communism and fascism. The group’s main aim was to increase patriotism amongst working-class women and prevent strikes and lockouts. In 1925, the group had 40,000 members. The following year, Flora led the Great Prosperity March, which demanded an end to the unrest which would soon peak with the General Strike.

Flora died on the Isle of Arran on 7th January 1949. Well-liked, witty, and innovative, she is well known as one of the most dynamic members of the WSPU. She continued campaigning for what she believed in even after women won right to the vote, and even in her old age she was a good-natured and determined woman. Although I disagree with her later politics, I wouldn’t mind being a bit more ‘Flora.’

Sources and Further Reading

BBC Scotland. “Ballots, Bikes and Broken Windows: How Two Scottish Suffragettes Fought for the Right to Vote. Last modified 6 February 2018, accessed 6 August 2018. Available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5cdhGvg5Lcy52KPV7xY7YBS/ballots-bikes-and-broken-windows-how-two-scottish-suffragettes-fought-for-the-right-to-vote

Cowman, Crista. “Drummond [nee Gibson; other married name Simpson], Flora McKinnon.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Last modified 6 January 2011, accessed 6 August 2018. Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/39177 [this reference requires a subscription to access].

Simkin, John. “Flora Drummond. ” Last modified January 2015, accessed 6 August 2018. Available at http://spartacus-educational.com/Wdrummond.htm

The Herald Scotland. “Belated Salute to the General.” Last modified 15th May 2001, accessed 6 August 2018. Available at http://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12168905.Belated_salute_to_the__apos_General_apos__At_last_a_memorial_is_to_be_erected_to__an_extraordinary_Scots_suffragette___as_Jennifer_Cunningham_discovers/

Wikipedia. “Flora Drummond.” Last modified 11 July 2018, accessed 6 August 2018. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flora_Drummond