Turbulent Londoners is a series of posts about radical individuals in London’s history who contributed to the city’s contentious past, with a particular focus of women, whose contribution to history is often overlooked. My definition of ‘Londoner’ is quite loose, anyone who has played a role in protest in the city can be included. Any suggestions for future Turbulent Londoners posts are very welcome. To celebrate the centenary of the Representation of the People Act, all of the Turbulent Londoners featured in 2018 will have been involved in the campaign for women’s suffrage. The third of my suffrage activists is Muriel Matters, an Australian actress, lecturer, and journalist with a flair for dramatic stunts.

All of the suffrage campaigners I have featured so far as Turbulent Londoners have been British. London has always been a city of migrants, however, and many of the activists involved in the campaign for women’s suffrage were born elsewhere. Muriel Matters was an Australian lecturer, journalist, actress, and elocutionist who put her flair for the dramatic to good use fighting for a right that South Australian women had had since 1894.

Muriel Matters was born on the 12th of November 1877 to a large Methodist family in Adelaide, South Australia. As a child she was introduced to the writing of Walt Whitman and Henrik Ibsen, who strongly influenced her political consciousness. In 1894, when Muriel was still a teenager, South Australia became the first self-governing territory to give women the vote on the same standing as men.

Muriel studied music at the University of Adelaide, and by the late 1890s she was acting and conducting recitals in Adelaide, Sydney, and Melbourne. In 1905, at the age of 28, Muriel moved to London to try and further her acting career. Leaving a country where women had the right to vote in all federal elections, Muriel arrived in a country where women could not vote at all. Facing stiff competition for acting work, Muriel also had to take on work as a journalist. She interviewed the exiled anarchist Prince Peter Kropotkin, and later performed at his home. Kropotkin challenged Muriel to do something more useful with her talents than acting–she later identified this as a defining moment in her life. She joined the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), a group which had broken away from the WSPU in 1907 because of the lack of democracy in the organisation. The President of the WFL was Charlotte Despard, a formidable woman who is one of my favourite Turbulent Londoners.

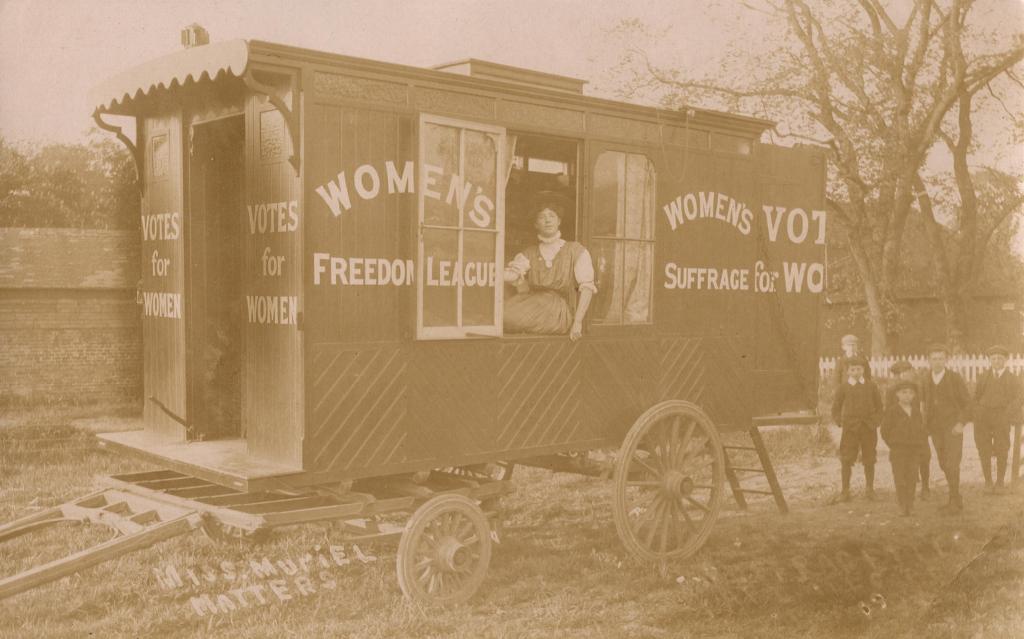

Between early May and Mid-October 1908, Muriel was the ‘Organiser in Charge’ of the first ‘Votes for Women’ caravan tour around the South of England. WFL activists visited towns in Surrey, Sussex, East Anglia, and Kent, with the aim of talking about women’s suffrage and forming new branches. Despite problems with hecklers, the tour was very successful, and many of the other suffrage societies would later run caravan tours of their own.

Not one to rest on her laurels, on the 28th of October 1908 Muriel took part in a dramatic protest at the House of Parliament organised by the WFL. They were protesting against an iron grille in the Ladie’s Gallery that obscured the view of the House of Commons and was seen as a symbol of women’s oppression. Muriel and another activist called Helen Fox chained themselves to the offending grille, and loudly lectured the MPs below on the benefits of women’s enfranchisement. The grille had to be removed so that a blacksmith could remove the two women. Released without charge, Muriel rejoined the protest outside the House of Commons, and was eventually arrested for trying to rush the lobby. The next day she was sentenced to one month in Holloway Prison.

A few months later, the state opening of Parliament on the 16th of February 1909 was marked by a procession led by King Edward. In order to gain attention and promote the suffrage cause, Muriel hired a dirigible air balloon. With ‘Votes for Women’ on one side, and ‘WFL’ on the other, she planned to fly over central London, showering the King and Parliament with pro-suffrage leaflets. The weather conditions and a poor motor meant that Muriel didn’t make it to Westminster, but she did fly over London for one and a half hours, dropping 56lbs of leaflets. The stunt made headlines all over the world.

From May to July 1910, Muriel embarked on a lecture tour of Australia. She was an engaging speaker, making use of illustrations and even changing into a replica of the dress she wore whilst in prison. She advocated prison reform, equal pay, and the vote. At the end of the tour, she helped persuade the Australian senate to pass a resolution informing the British Prime Minister Asquith of the positive experiences of women’s suffrage. In October 1913, Muriel helped persuade the National Federation of Mineworker’s to support women’s suffrage.

On the 15th October 1914, Muriel married William Arnold Porter, a divorced dentist from Boston. She decided to double-barrel her surname. In June 1915, she laid out her opposition to war in an address called ‘The False Mysticism of War.’ She argued that it was not an effective method of solving problems, and justifications for it were based on false pretences. She particularly objected to Christianity as a justification for war, and questioned the significance of nationality. Views such as these were extremely unpopular at the time, and it took great bravery to voice them.

In 1916 Muriel went to Barcelona for a year to learn about the Montesorri method of teaching, a child-centred approach which promotes the development of the whole child, including physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development. Muriel believed that access to education should be universal, and she took what she learnt in Barcelona back to charity work she was doing in East London. In 1922, she toured Australia again, this time advocating the Montesorri method.

In the 1924 General Election, Muriel ran as the Labour candidate for Hastings. She ran on a socialist platform, advocating a fairer distribution of wealth, work for the unemployed, and gender equality. She didn’t win- Hastings was a safe Conservative seat, and wasn’t won by Labour until 1997. The ability to stand in itself was victory enough for Muriel. After the election, Muriel and her husband settled in Hastings. William died in 1949, and Muriel died 20 years later, on the 17th of November 1969, at the age of 92. Provocative until the end, she was remembered locally as being partial to a spot of skinny dipping at the nearby Pelham Beach.

Australian-born Muriel Matters launched herself wholeheartedly into the the campaign for women’s suffrage in her adopted country. Her flair for dramatic acts of non-violent civil disobedience helped her attract valuable attention and publicity for the cause of women’s suffrage.

Sources and Further Reading

Fallon, Amy. “Muriel Matters: An Australian Suffragette’s Unsung Legacy.” Last modified 11 October 2013, accessed 8 February 2018. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2013/oct/11/muriels-neglecting-an-australian-suffragettes-unsung-legacy

Friends of Hastings Cemetery. “Muriel Matters Porter.” No date, accessed 8 February. Available at http://friendsofhastingscemetery.org.uk/mattersm.html

The Muriel Matters Society Inc. “About Muriel.” No date, accessed 8 February 2018. Available at https://murielmatterssociety.com.au/home-page/who-was-muriel-matters/

Wikipedia. “Muriel Matters.” Last modified 20 January 2018, accessed 8 February 2018. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muriel_Matters