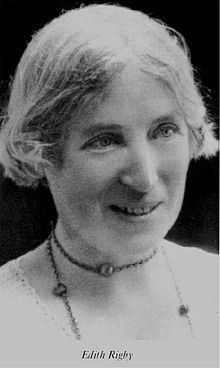

Regular readers of this blog will know that I usually write about Turbulent Londoners, women who participated in some form of protest or dissent in London. However, I have recently moved to Preston in Lancashire, so I have decided to celebrate the turbulent history of my new city. As I was learning about Preston I came across Edith Rigby, a social reformer and suffragette, whose activism rivalled any of the London suffrage campaigners.

Edith Rayner was born on the 18th of October 1872, one of seven children of a doctor. Although her family was quite well off, they lived in a working-class area, and Edith came to sympathise strongly with the poor and disadvantaged. She questioned the sharp divisions between Preston’s social classes, and devoted much of her life to improving the lives of working-class women, as well as fighting for women’s rights more generally.

It is though that Edith was the first woman to ride a bike in Preston, in the late 1880s. She was pelted with vegetables and eggs as she cycled around the town, but that did not put her off. In September 1893, at the age of 21, Edith married Dr. Charles Rigby. The couple moved into the elegant Winckley Square, which contained the kind of large, expensive homes that had led Edith to question the inequality between rich and poor in her early life. It seems likely that Charles was supportive of Edith and her beliefs–throughout her married life she was known as Mrs. Edith Rigby, rather than the customary Mrs. Charles Rigby. The couple adopted a two-year-old boy named Arthur in 1905, and by all accounts had a happy marriage.

In 1899, Edith founded St Peter’s School, which allowed working class women to continue their education after the age of 11. She was also critical of how Preston’s wealthy treated their servants. The Rigbys did employ servants, but they treated them well; for example, they were allowed to eat in the dining room and they did not have to wear uniforms. As the bicycle story might suggest, Edith was not afraid of causing a little scandal; she wore unconventional, practical clothing, and caused a stir by washing the front step of her house herself.

At the time, children started work in the local factories and mills at the age of 11 as ‘half-timers.’ Edith founded an ‘after-mill club’ for half-timer girls in Preston on Brook Street. The club was both educational and recreational , and activities included cricket, music, and trips to the swimming baths and theatre, as well as more traditional lessons such as debating. The trip to the theatre gave rise to the Brook Street Drama Society which performed An Enemy of the People by Henrik Ibsen, a play about corrupt local officials and the morality of whistle blowing.

Edith was also involved in a series of campaigns to help specific groups of female workers. For example, the women of the Woods Tobacco Factory suffered from illnesses caused by nicotine poisoning and poor ventilation in the factory. When they were forced to work an extra hour per day for the same wages, Edith stepped in. She persuaded Woods’ best customer, the Co-Operative Wholesale Company, to boycott Woods until working conditions improved. In 1906, she formed a Preston branch of the Women’s Labour League, a union for female workers.

In 1907, Edith founded a Preston branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the organisation founded by Emmeline Pankhurst to campaign for women’s suffrage in 1903. Edith was an active recruiter, encouraging members of the local Labour party to join the WSPU. Although soft-spoken, she was known for being incredibly persuasive. In 1908, Edith travelled to London to participate in a march on the Houses of Parliament. Along with 56 other women, Edith was arrested and sentenced to a month in prison. This was the first of seven prison sentences Edith would endure for the cause of women’s suffrage. She embarked on a hunger strike, and was subjected to force-feeding.

The following year, Winston Churchill, at this point President of the Board of Trade, visited Preston. Edith was arrested at a meeting at which Churchill spoke. After her release, she followed Churchill to Liverpool, where she smashed a window at a police station. For this, she was sentenced to two weeks imprisonment. In 1913, she threw black pudding at the local MP at a meeting in the Manchester Free Trade Hall. She chose black pudding because it was more demeaning than other foodstuffs usually used in such a protest, like milk or eggs.

Edith employed militant tactics to get her point across, even by the standards of the WSPU. On the 5th of July 1913, she planted a bomb in the Liverpool Cotton Exchange. No one was hurt, and the damage was minimal. Edith had planned it this way, because she wanted people to understand how angry the suffragettes were, and how much harm they could do if they wanted to. Edith turned herself in, and was sentenced to 9 months in prison. She also claimed responsibility for setting fire to Lord Levelhulme’s bungalow on the West Pennine moors just two days later, on the 7th July 1913. The fire destroyed valuable paintings and caused around £20000 worth of damage.

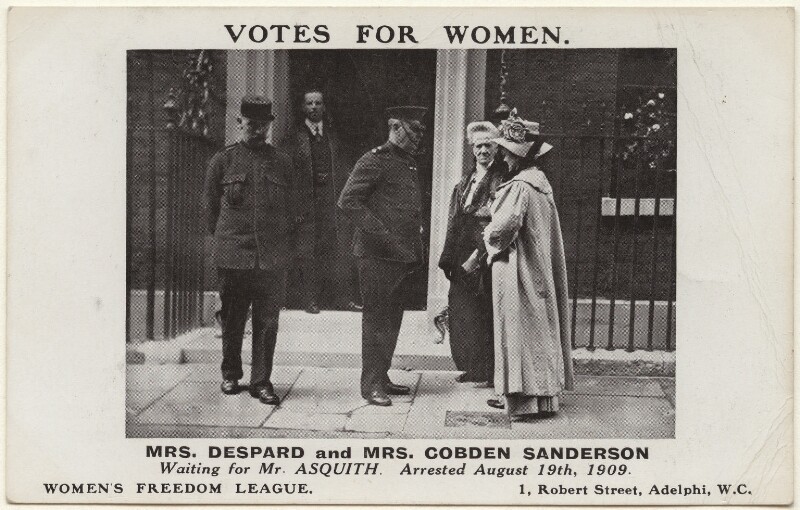

With the outbreak of World War One, the WSPU ceased campaigning and threw themselves behind the war effort. Edith disagreed with this decision, and joined the breakaway group the Independent Women’s Social and Political Union (IWSPU), setting up a branch in Preston. Although not opposed to the war like some groups such as the Women’s Freedom League and the East London Federation of Suffragettes, the IWSPU continued to campaign for the vote until it dissolved in 1918.

During the war, Edith bought a cottage outside Preston called Marigold Cottage, which she used to produce food for the war effort. Charles retired and lived with Edith at the cottage. Charles died in 1925, and Edith moved to North Wales the following year. During her later life, Edith became interested in the work of Rudolf Steiner, eventually forming her own Anthroposophical Circle. She died in 1950 near Llandudno, Wales.

Edith Rigby was a formidable woman, fiercely committed to her principles. She dedicated her life to fighting for women’s rights, particularly those of working class women, who were so frequently exploited in the factories of Lancashire. She was willing to take drastic action, and whilst I do not necessarily agree with her methods, I certainly admire her courage.

Sources and Further Reading

Caslin, Sam. “Why did Suffragette Edith Rigby Plant a Bomb at the Cotton Exchange in Liverpool?” University of Liverpool. Last modified 6th February 2018, accessed 20th March 2018. Available at https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/history/blog/2018/suffragette-edith-rigby/

Machel, Hilary. “‘Of Course, she was Years Ahead of her Time’: Preston Suffragette Edith Rigby.” Friends of the Harris. Last modified 25th June 2014, accessed 1st March 2018. Available at http://friendsoftheharris.tumblr.com/post/89842164634/of-course-she-was-years-ahead-of-her-time

Wikipedia. “Edith Rigby.” Last modified 18th February 2018, accessed 1st March 2018. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Rigby

Wikipedia. “Independent Women’s Social and Political Union.” Last modified 3rd December 2017, accessed 1st March 2018. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independent_Women%27s_Social_and_Political_Union