In a previous On This Day post, I wrote about the death of PC Keith Blakelock in the Broadwater Farm Riots in 1985. He was only the second police officer to be killed in a British riot since 1833. In June 1919, Station-Sargeant Green died of injuries received during a riot of Canadian soldiers in Epsom. The officer killed in 1833 was PC Robert Culley, who was stabbed in the chest during the Coldbath Field Riot over 150 years before. The response of the public to the two deaths in 1985 and 1833 was vastly different, demonstrating just how much the Metropolitan Police’s reputation with Londoners has improved since its foundation in 1829.

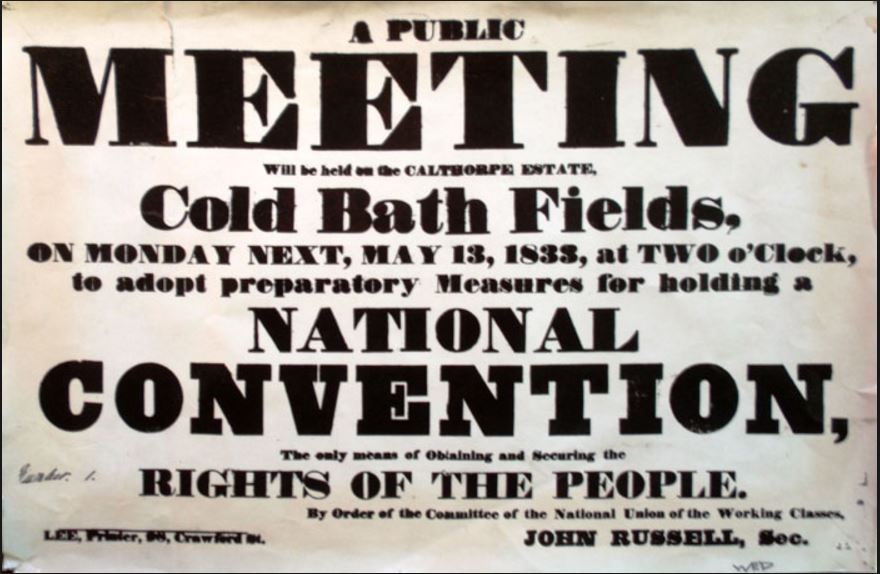

The Coldbath Fields Riot on the 13th of May 1833 was the first major clash between radicals and the young Metropolitan Police. The National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC) organised a demonstration in Coldbath Fields in Islington against the 1832 Reform Act. The Reform Act increased the number of men allowed to vote, but only by a small amount, and it didn’t go far enough for the NUWC. The Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne, declared the meeting illegal, but it went ahead anyway. On the afternoon of the 13th of May a large crowd had gathered, listening to speeches given from the back of open wagons.

After a while, a large detachment of police arrived and began to clear the crowd. The high number of police officers raised tensions, leading to shouted insults. The police trapped some of the protesters in nearby Calthorpe Street, who then attempted to fight their way out. In the ensuing chaos, three police officers were stabbed; Sergeant John Brooks, PC Henry Redwood and PC Robert Culley. Brooks and Redwood both survived, but Culley only made it to the nearby Calthorpe Arms before he died.

Robert Culley was one of the first men to join the Metropolitan Police, aged 23, when it was founded. Although the murderer wasn’t caught, the inquest into Culley’s death began two days later, in an upstairs room of the same pub where he died. The 17 men of the jury returned a verdict of Justifiable Homicide, arguing that the police had provoked the crowd with their violent approach to policing the protest. The men of the jury were local shopkeepers and householders, not radicals, and their verdict reflected the extensive mistrust and disregard that most Londoners felt for the Metropolitan Police at the time. Many resented the state intervention that the new force represented, and the jury became local heroes. The following month, a riverboat trip was arranged for them and their families to Twickenham, and crowds lined the river to cheer them on, despite heavy rain. In a similar way, George Fursey, the man who stabbed the other two police officers, was acquitted in his trial at the Old Bailey in July.

The public outcry and widespread condemnation after the death of PC Blakelock during the Broadwater Farm Riots could hardly seem more different to the reaction to the death of PC Culley 150 years before. The Metropolitan Police is not universally liked today, but it is hard to imagine the death of an officer during a protest receiving such a callous response. For better or worse, the police force has become part of the fabric of modern London in a way that might surprise an onlooker from the early nineteenth-century.

Sources and Further Reading

Moult, Tom. “The Metropolitan Police in Nineteenth-Century London: A Brief Introduction.” New Histories 3, no. 5 (2012). Available at http://newhistories.group.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/wordpress/the-metropolitan-police-in-nineteenth-century-london-a-brief-introduction/

Rowland, David. “The Murder of Police Constable Robert Culley.” Old Police Cells Museum. Last modified 18th October 2015, accessed 28 April 2017. Available at http://www.oldpolicecellsmuseum.org.uk/page/the_murder_of_police_constable_robert_culley

Webb, Simon. Bombers, Rioters and Police Killers: Violent Crime and Disorder in Victorian Britain. Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2015.

There are few dozen articles in old Australian newspapers, some copied from English papers, which have a different slant on these 1833 events ; Comparing that day to the Peterloo Massacre.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/232475583

Recent events :– Police attacks on 1980’s miners, Stonehenge hippies, the G-20 protesters (Ian Tomlinson death), and others show that the same tactics continue.

LikeLike

I believe your opening facts are incorrect regarding Keith Blakelock. He was not the first officer to be killed during a riot since “Coldbath Field”. At the end of the First World War, Canadian Servicemen who were billeted in Epsom, rioted in the town centre during which a Metropolitan Police Officer was murdered.

The officer is buried in the Town’s Cemetary on the Downs and there is a memorial to him in the Epsom Police Station Foyer.

LikeLike

Thank you for letting me know, I’ll look into it!

LikeLike

I notice you have not corrected your paper yet regarding the first death of a serving police officer since Pc Cully.

Regards

Matt Saunders

LikeLike

Hi, I am sorry for the delay. I did some research and you are absolutely right. I have amended the blog post accordingly. Thank you for letting me know, I had never heard of the Epsom riot before!

Hannah

LikeLike