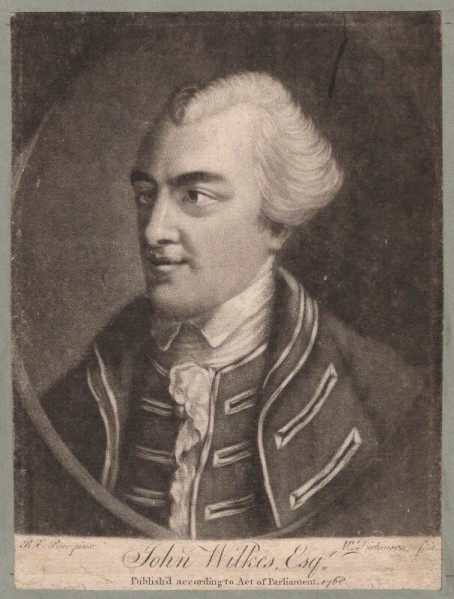

Most people have probably never heard of John Wilkes, but in the eighteenth century he was one of London’s most popular radicals. On the 10th May 1768, soldiers opened fire on some of his supporters outside the King’s Bench Prison in Southwark where Wilkes was being held. 6 or 7 people were killed, including bystanders, in an event that would become known as the Massacre of St. George’s Fields.

John Wilkes was a radical MP, and in June 1762 he started a newspaper, The North Briton, which was very critical of both the government and the monarchy. He was protected by parliamentary privilege, which means that MPs have legal immunity for things they do or say in the course of their duties. This only protected Wilkes up to a point, however, and he eventually went too far, publishing a poem that the House of Lords deemed to be obscene and blasphemous. They started the process of expelling Wilkes from the House of Commons, which would have removed his parliamentary privilege and left him open to prosecution. Wilkes fled to Paris before this could happen. In his absence he was found guilty of obscene and seditious libel and declared an outlaw on the 19th of January 1764.

Wilkes hoped that a change of government would lead to the charges against him being dropped. He ran out of money before that happened, however, and had to return to England. He wasn’t immediately arrested, as the government feared it would only increase his support base. Wilkes was elected as MP for Middlesex, but in April decided to waive his parliamentary privilege and hand himself over to the court of the King’s Bench. He was sentenced to 10 months in prison and given a £500 fine.

Wilkes was taken to the King’s Bench Prison in Southwark, on the edge of a large open space called St. George’s Field (an area stretching from Waterloo Station to Borough High Street today). As news of Wilkes’ imprisonment spread, his supporters began to gather on St. George’s Fields. The numbers increased daily, and by the 10th of May there were around 15,000 people there. Fearful of the large crowd, four Justices of the Peace requested military support, and a detachment of Horse Grenadier Guards were sent. This only increased tensions, however, as the crowd taunted the soldiers.

A group of soldiers chased one man who was being particularly offensive into a nearby barn. They opened fire, killing William Allen, an innocent bystander. As news of Allen’s death spread, the situation on St. George’s Fields only got worse. The Riot Act was read and more soldiers were called for, amongst fears that the crowd would attempt to break Wilkes out of prison. The crowd began to throw stones at the soldiers, who opened fire. In total, 6 or 7 people were killed, including another innocent bystander, and about 15 people were injured. Admittedly this isn’t a large number of casualties, but at the time it was quite significant. Understandably afraid for their lives, the crowd on St. George’s Field broke up, but as news of what had happened spread through London, sporadic rioting broke out across the city.

Two soldiers were charged with the murder of William Allen, but they were not convicted. Allen’s father presented a petition to parliament asking for justice for his son, which led to a debate about whether the government, who had supported the soldiers, was too oppressive. Nothing came of it though. In a letter to some of his supporters in America, Wilkes suggested that the massacre may have been pre-planned by the government, although there is no evidence of this. Wlkes was released from prison in March 1770. He was re-elected as an MP several times, and each time Parliament expelled him. Instead, he was appointed a Sheriff of London, becoming Lord Mayor in 1774. During the 1780 Gordon Riots, Wilkes fought against the rioters, which significantly damaging his reputation with the people and other radicals.

John Wilkes was a champion of anti-government feeling and the right to free speech. His popularity with the people of London terrified the authorities, which may explain why the situation on St. George’s Fields escalated so quickly. Or, it could just be an example of poor policing exacerbating a crowd, which has happened on many other occasions. Either way, it was a dramatic and deadly episode in the constant struggle between the authorities and the people for London’s streets.

Sources and Further Reading

German, Lindsey, and John Rees. A People’s History of London. London: Verso, 2012.

Harris, Sean. “The Massacre of St. George’s Fields and the Petition of William Allen.” UK Parliament. Last modified 31 October 2016, accessed 23rd April 2019. Available at https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/petitions-committee/petition-of-the-month/the-massacre-of-st-georges-fields-and-the-petition-of-william-allen-the-elder/

Simkin, John. “St. George’s Fields Riot.” Spartacus Educational. Last modified August 2014, accessed 23rd April 2019. Available at https://spartacus-educational.com/LONstgeorge.htm

TeachingHistory.org. “Boston’s Bloody Affray.” No date, accessed 7th May 2019. Available at https://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/23472

White, Jerry. London in the Eighteenth Century: A Great and Monstrous Thing. London: The Bodley Head, 2012.

Wikipedia. “Massacre of St George’s Fields.” Last modified 15th March 2019, accessed 23rd April 2019. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massacre_of_St_George%27s_Fields