Some bits of your PhD are tough, and some bits are damn hard. I have been going through a particularly difficult stretch recently; I am coming into the last few months, and everything is taking about twice as long as I need it to. On some days, it is difficult to remember why I signed up for this in the first place. But I do love my PhD, and I want to hold on to that, so I made a list of all the things about my PhD that I enjoy:

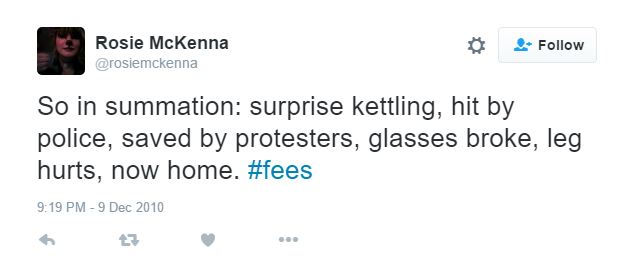

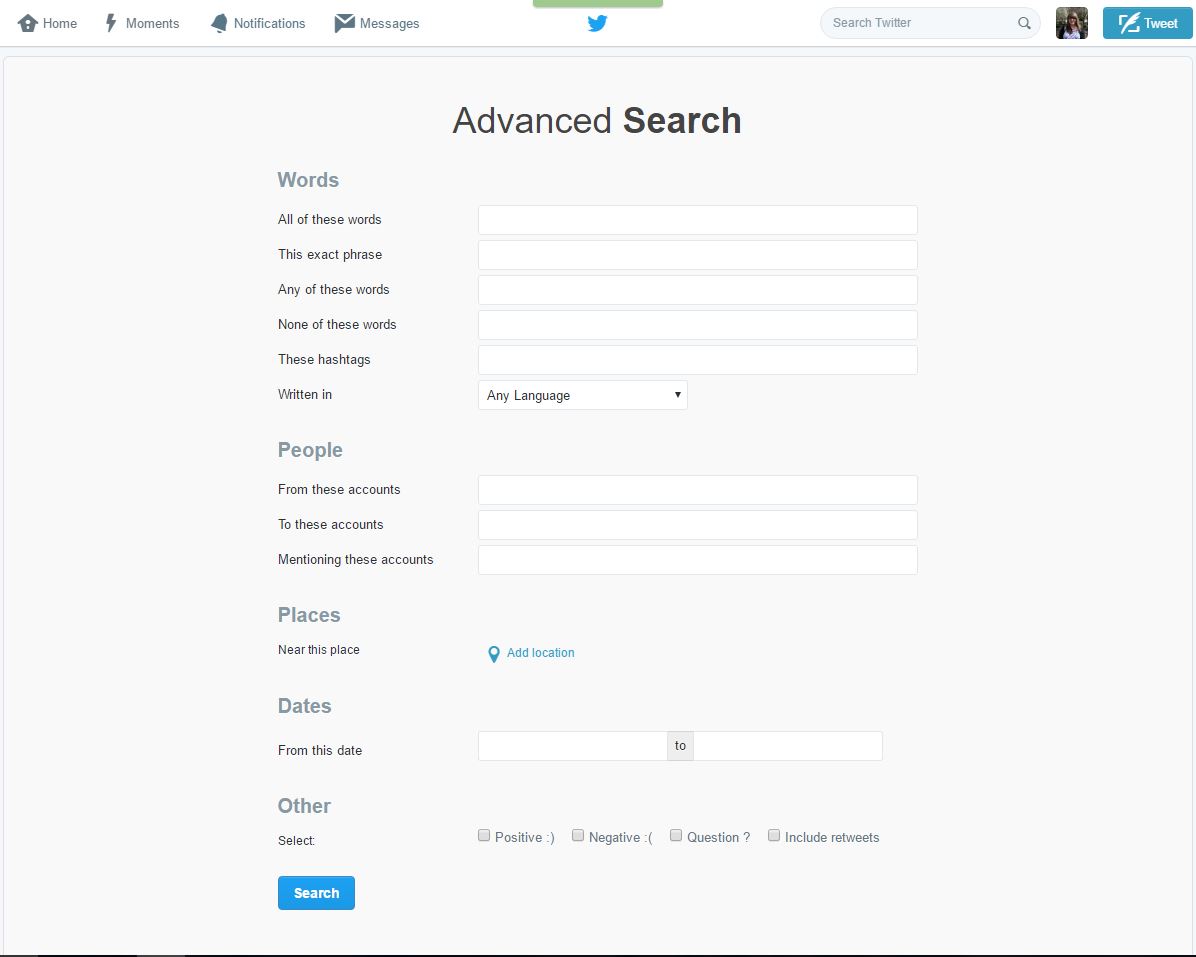

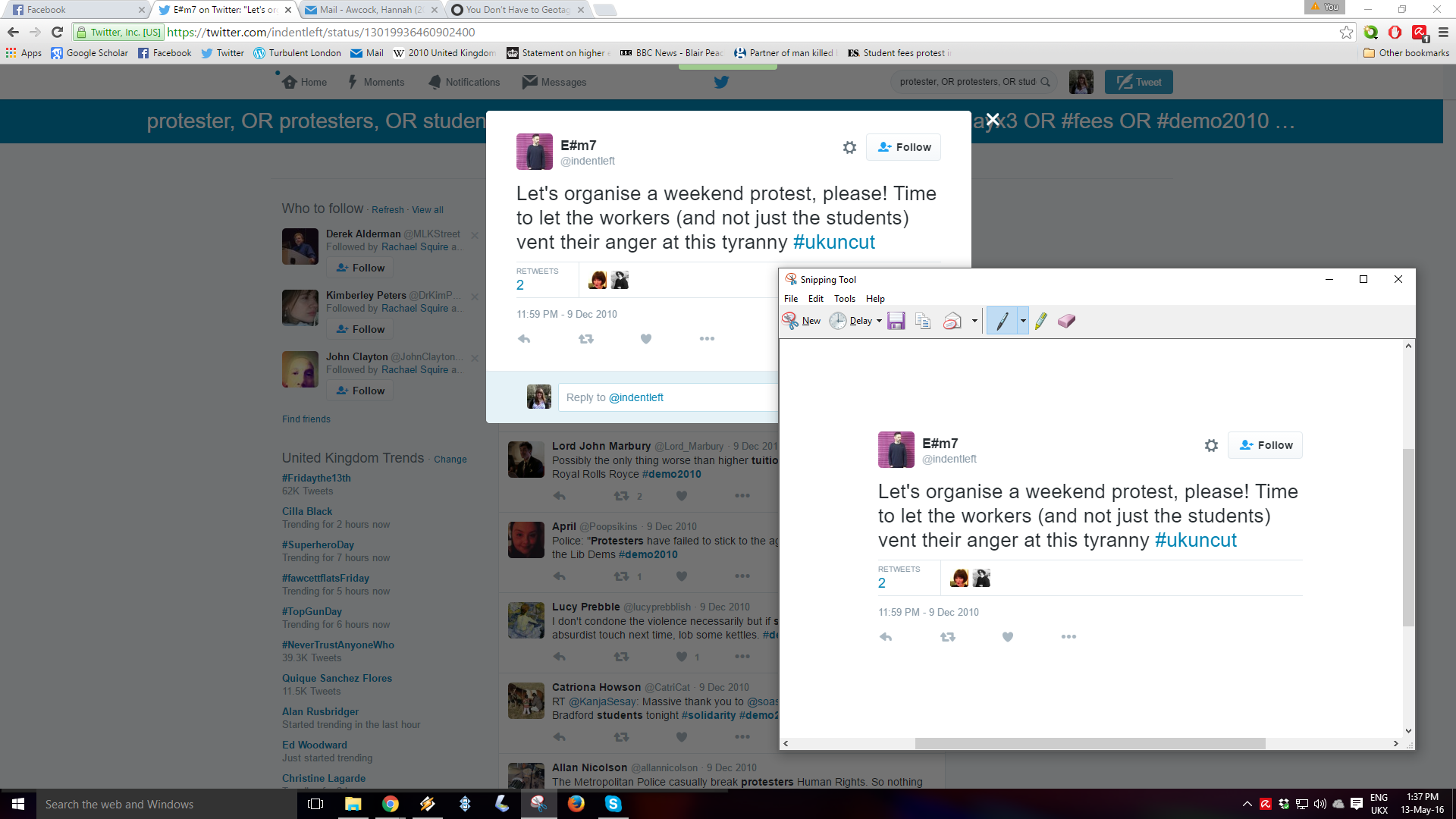

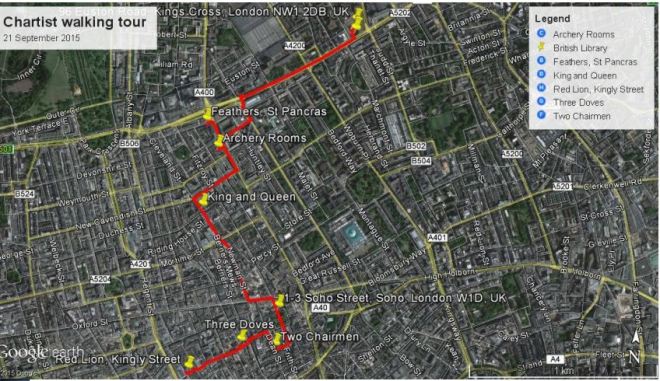

1. My topic. I have always loved history and geography, and protest is a topic I’ve been interested in since the Student Tuition Fee Protests in 2010. I was an undergraduate, and it was the first time I got involved in protest. The connections between my experiences and my studies in Geography were obvious. London is a fantastic city to research as well, I love being able to spend my days finding out more about the people and events that have shaped the history of one of my favourite cities in the world.

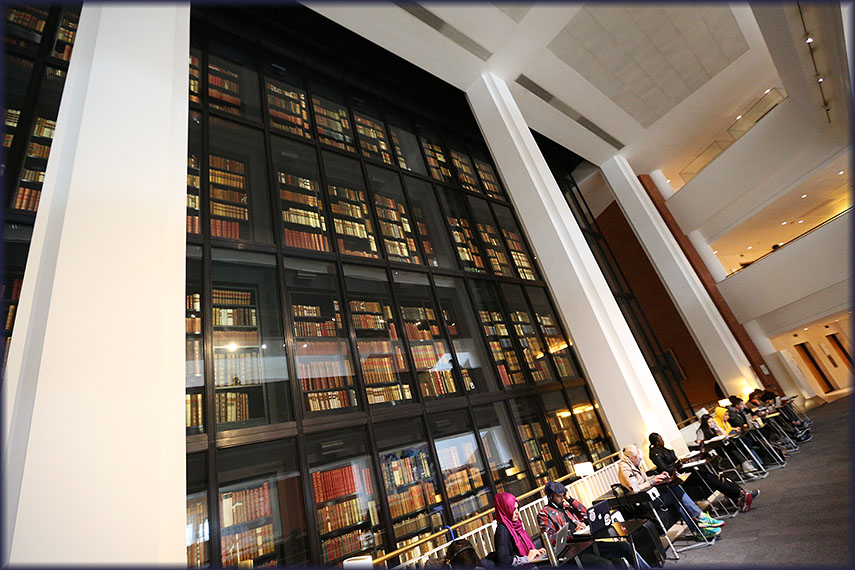

2. Working in the archives. Whilst I was conducting research on the Gordon Riots, I spent quite a bit of time in the Rare Books and Manuscripts room at the British Library. I consulted the diary of John Wilkes, radical politician and perpetual pain in the neck of the government in the middle of the eighteenth century. I got a little thrill knowing I was touching pages that he had written. I also just enjoy spending time in libraries and archive reading rooms, surrounded by books, in peace and quiet. The Bishopsgate Institute Library in London is a particular favourite of mine, it is exactly what a good library should look like!

3. Going to conferences. Conferences are long and tiring, but I really enjoy them. They are great opportunities for finding out about the latest ideas and research, and for meeting new people, and catching up with others that you met at previous conferences. Doing a PhD can be a lonely experience, and conferences are an enjoyable social respite. They can also be an excuse to travel; last year I was lucky enough to go to Chicago for the Annual Conference of the Association of American Geographers, and I had a fantastic time exploring the city.

4. Teaching. I have been lucky enough to get plenty of teaching opportunities during my PhD. I’ve had a go at marking, demonstrating, lecturing, and running seminars, and I’ve enjoyed most of them. I’ve also helped on the undergraduate field trip to New York.

5. Writing this blog. There have been several occasions over the last few months when I have considered taking a hiatus from Turbulent London, or at least decreasing the frequency of posts in order to concentrate on my thesis. Every time I have decided not too, because I enjoy it too much. The writing style comes to me more easily than the formal academic style, and it feels great when someone responds to a post. So I’m going to try and keep it going for as long as I can.

So there you have it; 5 reasons why I love my PhD. I think it’s really important to be open about the negative elements of postgraduate study and academia, but sometimes you just need to stop and take stock of all the good things.